Opportunities for Investing in Inclusive Business (IB) in South East Asia

By: CHONG Zheng Ying (CSR Asia) and Armin BAUER (ADB)[1]

This blog is part of a series of articles on inclusive business in Asia written by a wide range of experts in the run up to the ADB’s 2nd Inclusive Business in Asia Forum in Manila. See the full series here.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is planning to launch a report on “Impact Investing in Southeast Asia: An Opportunity to Invest in Inclusive Business”. The report gives an overview of IB investment and market opportunities in the region. The lack of information on the opportunities of the IB market is a key reason why larger and medium-scale domestic companies in Southeast Asia are reluctant to venture into IB.

Southeast Asia needs IB for making its growth more inclusive:

Economic growth in Southeast and East Asia has been strong in the last two decades, and the region is a success story for poverty reduction. However, the growth path did not create sufficient quality jobs and services and goods relevant for the poor and low income people. Governments and private sector realize that companies with specific business models can address this gap, thereby creating shared value for society and the shareholder. The BoP in emerging East and Southeast Asia is a huge market of 1.3 billion people with a purchasing power of $4.7 trillion and large unserved needs. What is needed are more innovative business models with high productivity, developed specifically for the BoP’s needs and allowing them to create income above the competing market rates of informal sector and middlemen, and access health, education, housing, water and sanitation and financial services which effectively improve their living conditions. Exploring this new markets is of particular interest for visionary business leaders with double or tripe bottom-line orientation.

Southeast Asia faces specific challenges for generating more IB. Compared to South Asia and Latin America, there are very few IB deals so far in Southeast (and even less in East) Asia. While there are huge opportunities at the BoP market, IB in the region is still a new phenomenon. High cost of large mile distribution, the unfamiliarity with the purchasing and living behaviours of the poor, the large informality of the market and the high perceived risk to invest, government restrictions, the difficulties of finding an affordable price point while maintaining high product/service quality for this market segment, and lack of analytical understanding how to maximize social impact, are common challenges for all IB markets globally. However in Southeast Asia, IB investments remain nascent also due to other reasons such as high risk aversion, lack of a wide-spread culture of innovation and leadership, and an environment in which caring for the poor is done actively by private sector through philanthropy, or/and expected to be delivered by the government. [2]

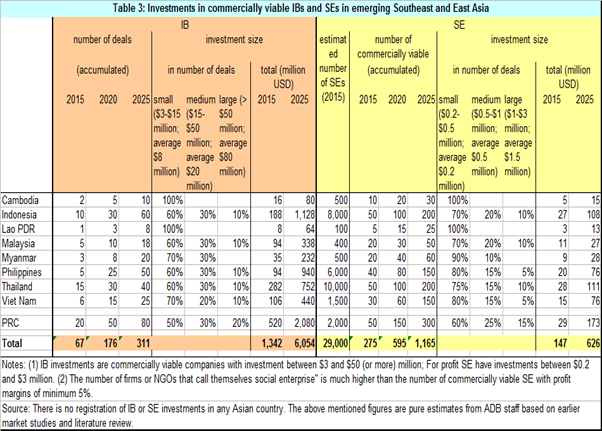

Large growth potential: The ADB estimates that excluding the microfinance sector, the number of mature, “investment-ready” inclusive businesses in the region is expected to triple in the next ten years, from an estimated 60 in 2015 to over 300 investment-ready companies across the region by 2025. The majority of these potential deals (60-70%) are likely to be small - in the $2-15 million range; 20-30% are estimated to be of medium-size ($15-$50) million range; and about 10% to be large (over $50 million). This could mean a potential market opportunity in the next 10 years of about $6-7 billion, up from perhaps $1 billion in 2015. China is likely to account for close to a quarter of estimated growth in the IB sector, but large new opportunities are also possible in Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, followed by Viet Nam and Myanmar. The investment opportunities in commercially viable IBs is expected to be about 10 times higher than in SE. While the expected $6-7 billion investment opportunity in IB can be realized in all sectors, it is likely that three sectors will take the lead: agribusiness (about 26% of the investments), finance and telecom (31%), health and education (28%), followed by investments in housing and urban utilities (7%), tourism, trade, and manufacturing (6%), and energy and transport (1%).

Current state of impact investing: It is estimated that in 2015 about $3.6 billion has been placed in Southeast Asia by impact investors, of which $0.6 billion is from development financial institutions like ADB and IFC (these are typically IB investments), $2.3 billion by fund managers and 0.3 billion by commercial banks (both typically in companies with assumed trickle down effects on the environment or on people), and 0.07 billion by pension funds. Grant financed programs comprise $0.2 billion from foundations, $0.07 billion by development partners, and $0.004 billion by other donations.[3]

Philanthropy and CSR: The region has a very strong philanthropic orientation with more than 900,000 high net worth individuals[4] donating large sums for small and often ad hoc social or environmental projects. At the same time, many companies engage the poor through corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities in their neighbourhood. However these philanthropic and CSR activities are small in scale, often questionable in design and impact, and do not create systemic change. They are also not financially sustainable, because the CSR and philanthropic funding is not generated through a core business model related to the goods and services that are being offered to the BoP.

[1] Chong Zheng Ying is Senior Project Manager at CSR Asia (Singapore); Dr. Armin Bauer is Principal Economist and Coordinator of ADB’s Inclusive Business Initiative. The study was prepared by Caterina Meloni (consultant) and Armin Bauer (ADB). We thank colleagues from Credit Suisse for their valuable inputs.

[2] The chart is taken from the forthcoming report on Impact Assessment. The figures refer to purchasing power parity per person per day before the recent upgrading of the poverty lines by the World Bank.