A behavioral approach to upgrading in food value chains

This note presents an analytical framework on the adoption of upgraded practices by actors in food value chains. It forms the basis of a practitioners’ handbook on promoting the optimal adoption of agro-inputs in sub-Sahara Africa, currently under development at FAO. The handbook will be based on a rich set of case studies and provide concrete solutions to common problems.

Having a sustainable impact at scale requires the non-temporary adoption of upgraded practices by large numbers of actors. This implies in turn that we need to understand fully all that stands in the way of such behavioral change. Only when we know this, can we design effective upgrading strategies.

Applied to the problem of a suboptimal adoption of quality agro-inputs by smallholder farmers, we present a two-step analysis:

- identify the core problems, i.e., the immediate causes; and

- identify the underlying causes for each core problem, i.e., the root causes.

Bearing in mind a systemic approach whereby all factors are interlinked, it is worth to note that one cause may result in more than one problem and that one problem may have multiple causes.

STEP 1: Identify the immediate causes of a suboptimal adoption of agro-inputs by farmers

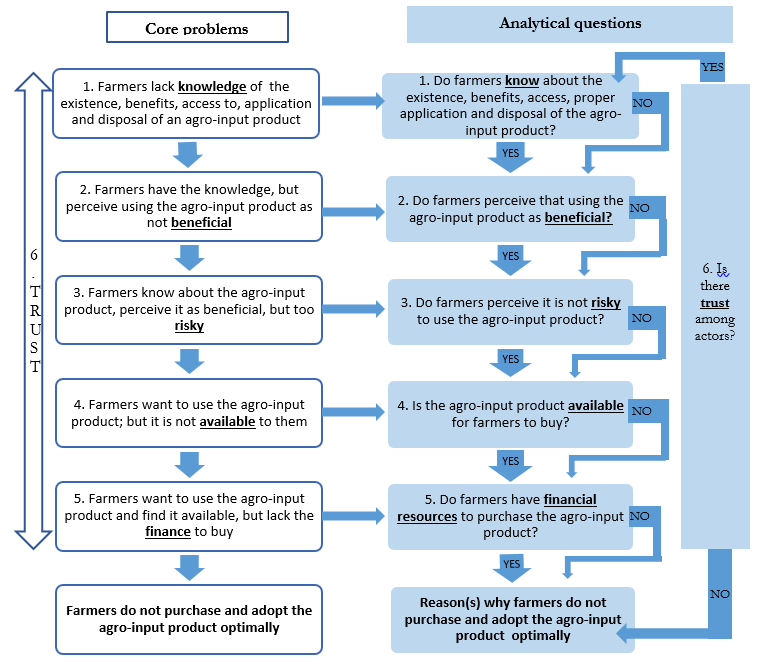

Figure 1 stylizes the logic of a farmer’s decision-making process regarding agro-input adoption. Development practitioners and analysts could use this flow chart as a specific, logical sequence of six yes/no questions to guide their analysis into why farmers are not adopting agro-inputs in an optimal way. Core problems are exposed one by one. Specifically:

- A “YES” answer to an analytical question means the core reason for farmers’ decision not to use agro-inputs does not lie in that question; and hence, logically, the next question will be asked.

- A “NO” answer to an analytical question means one core reason for farmers’ decision not to use agro-inputs lies in that area. The next questions will still be asked to identify whether the reason for farmers’ decision not to use agro-inputs also lies in the next areas.

Six possible core problems are identified, related to: (1) farmer knowledge; (2) perceived benefits; (3) riskiness; (4) availability; (5) financial feasibility; and (6) trust, as a crosscutting issue. These core problems and their root causes indicate the demand-related, supply-related and systemic factors that need to be addressed in order to achieve sustained behavioral change.

Farmer knowledge – To start, farmers will not demand agro-inputs if they lack the knowledge about the existence of the agro-inputs, the benefits that they can bring about, how to get access to them, or how to use and dispose of them correctly.

Perceived benefits – Farmers will not purchase and use agro-inputs if they do not perceive sufficient benefits associated with using the agro-inputs relative to the costs. The costs of purchasing and using agro-inputs may be perceived as too high, or the profits perceived as too low. Furthermore, non-monetary costs, such as negative social impacts associated with adoption, may get in the way as well.

Source: Authors

Riskiness – Even if farmers know about the agro-input product and perceive that using it is general beneficial, they may not use it if they perceive the associated risks as too high. For example, profits may be too uncertain due to natural environment-related yield variability, volatile markets of agricultural produce, or limited access to such markets. Even before use, there is the perceived risk of low agro-input product quality (e.g., counterfeit products).

Availability – Even when farmers are ready to purchase the agro-input, they may not be able to do so because the product simply is not available to them for a variety of reasons: no nearby dealer stocks it (at the right time); minimum order volumes are too big; the product specifications are not the right (or preferred) ones; or critical complementary products are missing (e.g., fertilizer and hybrid seeds, chemicals and spraying equipment).

Financial feasibility – Even when the first four issues – farmer knowledge, perceived benefit, riskiness, availability – do not pose any constraint to farmers’ decision to use agro-inputs (or packages of agro-inputs), farmers still may not purchase agro-inputs because they lack the finances to buy. Agro-inputs represent a cash expense and smallholder farmers often face significant cash constraints.

Trust – Even when these first five constraints are addressed, adoption may still not take place because there is insufficient trust among stakeholders in the agro-input supply system. The level of trust is a governance issue that takes time to build and that will motivate value chain actors and supporting service providers to either participate in or to withdraw from a value chain. Trust is multifaceted, including the bilateral trust between two value chain stakeholders (e.g., between input importers and agro-dealers regarding contracts, or between public and private actors regarding policies) as well as the multilateral trust between multiple value chain stakeholders (e.g. between financial institutions, agro-input suppliers, and agro-dealers).

STEP 2: Identify the root causes of a suboptimal adoption of agro-inputs by farmers

Once we have identified the core problems, we need to identify root causes for asking “why” questions:

- Why do farmers lack knowledge?

- Why do farmers perceive that it is not sufficiently beneficial to use agro-inputs?

- Why do farmers perceive that it is too risky to use agro-inputs?

- Why are agro-inputs unavailable for farmers to buy?

- Why is it financially unfeasible for farmers to buy agro-inputs?

- Why isn't there trust among stakeholders in the agro-input supply system?

Let us take the first of these questions as an example. Farmers’ attainment of knowledge depends on two factors: (i) their access to channels of information; and (ii) their ability and willingness to absorb the information provided through such channels. The root causes of these two sub-problems (i.e. lack of access to channels of information, lack of ability and willingness to absorb the information) can include supply-related and systemic causes.

Examples of supply-related causes are agro-input product design and packaging issues, a lack of promotional activities, a lack of complementary services such as soil analysis, agro-dealers who lack knowledge on the products they sell, and so on. Examples of systemic causes are a lack of quality and effectively provided extension services, weak physical infrastructure such as roads and ICT networks, strongly embedded traditional practices, and so on.

From analysis to design

With root causes identified, effective catalytic support programs can be designed. These can build on decades of development work for innovative solutions (success stories and lessons learned). For example, if a lack of farmer knowledge was a core problem, possible commercially or fiscally viable solutions include:

- new modalities for technical assistance (e.g., through agro-dealers in shops and phone-based);

- new promotional tactics (e.g., crop-cycle synched demo days with free samples and discount coupons for farmer communities);

- working with manufacturers and dealers on improved input product design (e.g., clearer use instructions on packaging);

- or entirely new business models (e.g., 1ha turn-key bundled packages of input, services, technical assistance and finance).

Based on a rich set of case-studies, the FAO handbook under preparation presents a problem solver guide that systematically goes through the core problems and main possible root causes for the sub-optimal adoption of inputs by smallholder farmers and provides concrete solutions (ideas and field-tested) that may be applied by development practitioners.