Facing The Poverty Tsunami: How Business Can Support the Lives, Livelihoods and Access to Learning of the Most Vulnerable People and Communities

The Poverty Tsunami: COVID, Conflict and Climate Change

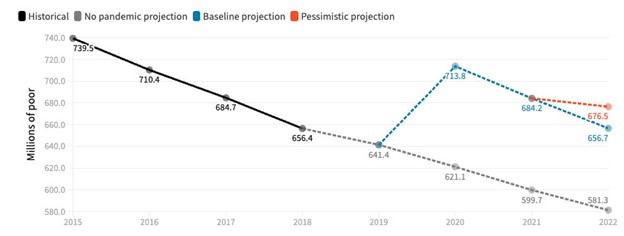

COVID, conflict and climate change are among a confluence of challenges driving a tsunami of poverty that is already crashing into the lives of vulnerable people and communities around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures to contain its spread led to 97 million more people living in poverty in 2020; with the 2021 projection revised upwards to 711 million and the impact expected to be long-lasting. The pandemic abruptly halted a steady near-25-year decline (by over 1 billion) in the number of people living in extreme poverty. Adding in inflationary pressures and the impact of the war in Ukraine, the World Bank is now estimating an “additional 75 million to 95 million people living in extreme poverty in 2022, compared to pre-pandemic projections”.

While vaccine roll-out through COVAX has gained momentum, with over a billion doses delivered, there is still a long way to go. As Gavi, the global vaccine alliance and co-lead of COVAX, says, “Hundreds of millions of people, mainly in lower-income countries, remain unvaccinated and unprotected, while the virus continues to evolve in uncertain ways”. Longer-term, The Brookings Institution suggests the impact of the pandemic on poverty could be to “accentuate the long-term concentration of poverty in countries that are middle-income, fragile and conflict-affected, and located in Africa”.

Meanwhile, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which unleashed appalling suffering on Ukrainians, has also had a dramatic knock-on effect worldwide. Both countries are major suppliers of energy, food and fertilisers, and supply disruptions have further driven up global prices and aggravated the global cost-of-living crisis. A report by the World Bank suggests that the war alone could push energy prices up by 50 per cent and food prices by 37 per cent. For some countries, the dependency for staple goods is striking; Sudan, for instance, relies on the two countries for 80 per cent of its wheat imports and 95 per cent of its sunflower oil. Chatham House analysis of the impact of the war states that “high prices for energy and food pose immediate threats to human security, particularly among low-income and vulnerable populations in all economies and against a backdrop of post-pandemic inflation and limited fiscal capacity.”

Overlay on this the added risks from climate change. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, more than 40% of the world’s population are “highly vulnerable” to climate change, with those “people and ecosystems least able to cope…being hardest hit”. According to the World Bank, climate change could drive 130 million people into poverty over the next decade. Around the world, low-income communities tend to be more exposed to extreme weather events because of where they live or the sectors in which they work, while lacking the resources, social safety nets or insurance to mitigate the impacts. The World Health Organisation estimates that “between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress.”

The Many Dimensions of Poverty

To fully understand the impact of these challenges creating the poverty tsunami, we need first to understand what poverty is. At one level, of course, poverty is a lack of enough resources to afford basic needs, such as food, water and shelter - in absolute terms or relative to others in society. Extreme poverty is defined by the World Bank (in absolute terms) as people living below the International Poverty Line of $1.90 per day, with those living on $1.90 to $3.10 defined as the “moderate poor”. Relative poverty is typically seen as less than 50-60% of a country’s median income.

However, in practice, poverty has many dimensions. When asked, poor people describe poverty as more than simply not having enough money. The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) includes health (nutrition and child mortality), education (years of schooling, school attendance) and standard of living (type of cooking fuel, as well as access to sanitation, drinking water, electricity and housing). The 2021 MPI found that across 5.9 billion people living in 109 countries studied, 1.3 billion - one in five - live in multidimensional poverty.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reflect the multidimensional nature of poverty. SDG Goal 1 is to “End poverty in all its forms everywhere”, with target 1.2 being to reduce by half the proportion of women, men and children living in poverty in all its dimensions, according to national definitions, by 2030. Understanding the different dimensions of poverty and their interlinkages is key to tackling it and tracking progress. Many countries now report on multidimensional poverty, and companies such as AB InBev and CEMEX are starting to apply this approach. Citi and SOPHIA Oxford recently published a guide for business and investors. Here at Business Fights Poverty, we see poverty as multidimensional, with our focus on the lives, livelihoods and access to learning of the most vulnerable people and communities.

Focusing on Equity

The level of inequality in a country can reduce the positive impact of growth on poverty. The effect of a one per cent increase in income levels can vary from a 4.3 to 0.6 per cent decline in poverty, depending on how unequal the country is. Equality of access to the assets - by an individual or group - is essential in shaping opportunities. However, equality (having the same resources or opportunities) is not enough. The key is equity: with each individual or group having access to the resources and opportunities they need, given their circumstances, to reach an equal outcome.

During the pandemic, deep-seated inequities, such as by gender and race, have shaped the impacts. A gender analysis of the war in Ukraine by CARE International UK demonstrates the distinct impacts on women and men. An article we recently commissioned with Avon on gender-based violence in Ukraine shows the threats that women and girls face in conflict settings. Existing inequities mean that climate change, too, has very uneven impacts, and the green transition has very different implications and opportunities. The 2021 MPI, which focused on “unmasking disparities by ethnicity, caste and gender”, found that in some cases, “disparities in multidimensional poverty across ethnic and racial groups are greater than disparities across geographical and subnational regions”. For example, in India, five out of six people living in multidimensional poverty are from lower tribes or castes. Globally, around two-thirds of multidimensionally poor people live in households where no woman or girl completed at least six years of schooling.

At its heart, the poverty tsunami reflects the lack of voice for particular groups. Putting people at the heart of fighting poverty must include listening to the voices of previously marginalised groups: strengthening their ability to take action, be listened to and participate.

Building Resilience

We cannot understand poverty outside the vulnerable context in which poor people live. This context includes trends (such as shifts towards mechanisation), shocks (such as the three challenges of COVID, conflict and climate change) and seasonality (such as of prices and employment opportunities). Poor people do not have sufficient assets to provide them with resilience to bounce back and recover after setbacks now and in the future.

How far below the poverty line they are also matters. Even if they are not currently living in poverty, many households are vulnerable to being pushed into poverty; one event - such as the loss of a job or the death of a family member - can be enough to push them into poverty. Poverty lines measure poverty at a moment in time and do not capture this dynamic element of vulnerability. For this reason, some argue that we need to quantify vulnerability to poverty. For example, the Vulnerable Poverty Line defines a household as vulnerable if they have a 50-50 chance of experiencing one episode of poverty in the near future. Applied to Indonesia in the late 1990s, it was found that in addition to the 20 per cent of the population that was poor, a further 10 to 30 per cent was at substantial risk of poverty.

Building the resilience of people and communities is, therefore, key to fighting the poverty tsunami. Essential tools include microinsurance and financial inclusion, social protection and adaptive safety nets, and, more generally, building poor people’s stock of assets: the more assets people have, the more resilient they will be. Importantly, inequity, in terms of an individual’s or group’s access to assets and other sources of resilience, can exacerbate their vulnerability.

The Role of Business

Economic growth is the most powerful way of lifting people out of poverty across its multiple dimensions. The data shows how, over 200 years, as incomes have grown, extreme poverty has fallen. The weak global growth outlook is therefore particularly worrying. The Economist predicts that “As the contours of the post-pandemic landscape come into focus, a lost decade—a period of slow growth, recurring financial crises and social unrest—for the world’s poorer countries looks increasingly plausible.”

Above all, then, businesses can fight poverty by helping drive growth. However, the extent to which growth in a country reduces poverty depends on how poor people can participate in and benefit from the growth process and the opportunities it creates. One key opportunity generated by growth is jobs. While getting a job can be a key route out of poverty, having a job does not guarantee a decent standard of living. In sub-Saharan Africa, 38 per cent of the employed population lived in extreme poverty in 2018. Next month, we will be publishing a report with the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership and Unilever on the robust moral and business case for living wages.

While contributing to growth is important, there is more that businesses can and should do, alongside government and civil society. The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework is helpful here. It recognises that people’s access to five assets shapes their livelihood opportunities (and ability to participate in the growth): human capital (e.g. knowledge and health), social capital (e.g. networks and relationships), natural capital (e.g. land and water), physical capital (e.g. housing and energy), and financial capital (e.g. savings and money). The economic, social (e.g. gender norms), policy and political environment shape people’s access to assets and what they can achieve with them. Businesses can help tackle poverty by building one or more of these assets or tackling the broader systemic level constraints through cross-sector partnerships. The nature of economic growth matters too; growth or business investment that undermines natural capital is not sustainable. Kate Raworth’s concept “Doughnut Economics” captures the need to meet social needs without overshooting planetary boundaries.

At Business Fights Poverty, we see business as having a powerful role to play: through (and especially through) its core business (e.g. decent jobs, responsible sourcing and investment that drives inclusive growth), as well as its advocacy and community investment*. Beyond the clear moral imperative, we believe fighting the poverty tsunami makes business sense, for example, by strengthening the resilience of supply chains or spurring innovation that serves the “base of the pyramid”. Given the complex nature of poverty and the systemic barriers people face, our view is that we need to collaborate across business, government and civil society with a new sense of urgency and purpose. We also believe we have to listen to the voices of those most proximate to the challenges we are tackling, and we are committed to this in our approach.

According to the UN, COVID may have set back progress in tackling global poverty by nearly ten years. Together with conflict and climate change, the world faces a poverty tsunami - a huge wave of poverty on a scale that we haven’t seen in a generation. Driving equity and building resilience are crucial to fighting this new wave of poverty, and business must play its full part.

* The three levers for business impact were developed by Jane Nelson, Director of the Corporate Responsibility Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School.

This article was originally published by Business Fights Poverty.