Girls and Business in Context in East Africa: 5 Key insights

In East Africa, adolescent girls (aged 10-19) face unique challenges that can range from experiencing time poverty due to burdensome responsibilities for domestic chores, to having less access to financial services than their male peers. However, girls are also incredibly resilient and persistent – they don’t give up on their dreams easily! SPRING believes that business has a role to play in turning these challenges into opportunities for girls.

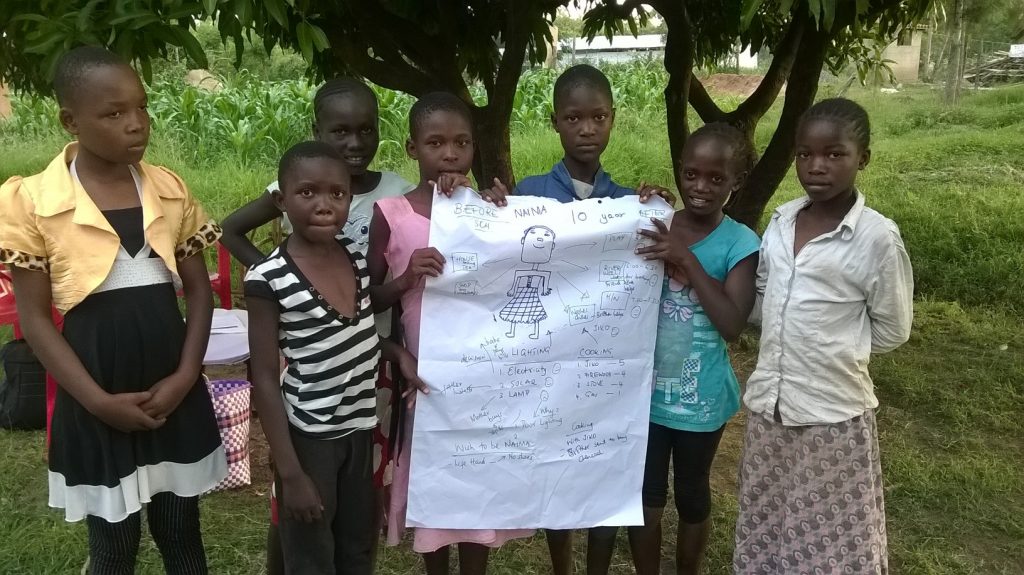

To support our businesses in East Africa to design products, services, and business models that meet the needs of adolescent girls, we started by developing a deeper understanding of girls’ lives in context: their aspirations, opportunities, challenges and enablers. We developed Sector Guides for Girl Impact, and followed these with on-the-ground qualitative research and insights gathering with small groups of target girl consumers and their key influencers and gatekeepers, highlighting key issues through girls’ own stories and voices.

Research design

We explored girls’ lives in six main areas: agriculture, energy, mobile technology and access to media, health, mobility and transportation, and saving and spending. We went to rural, urban and peri-urban areas in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. Our aim was to learn about girls’ aspirations, the aspirations others have for them, and the barriers to and enablers of girls’ access to products, service and opportunities that could enable them to earn, learn, save and keep safe. We spoke with a wide range of girls and others important in their lives, including mothers, fathers, boys, and service providers.

Age segmentation

When designing research and business solutions for girls, SPRING recognizes that girls are not all the same. Whether they are living in an urban or rural area, are in-school or out-of-school, married or unmarried, and their household situation, can impact, for example, their aspirations, ways they spend their time, their autonomy, mobility, education, and work opportunities. Their age is also important. Girls aged 10-13 are often still in school, with high hopes for their education and future. 14-16 year olds go through a transition where they begin to take on more adult roles and responsibilities; many girls lives change radically during this time. Girls aged 17-19 tend to fall into two extremes: those in school and unmarried, and those out of school and married, whose options are far more limited. It was important to speak to a range of girls in order to better understand demographic and socio-economic differences and similarities.

Findings

Five key insights emerged:

1) Social norms are often the biggest barriers in girls’ lives, but change is afoot.

Girls’ lives are shaped by social norms - the ‘unwritten rules’ and expectations that regulate their participation in their families and communities, as well as their access to growth opportunities.

Girls in Ethiopia, for example, shared that they are expected to help with household chores, to be obedient, perform well in school, smile, and seek approval and permission for everything they do. However, parents highlighted that they think children are far more independent now than in their generation, that education is more important, and some also felt that girls being financially independent is important.

Businesses should consider: To reach girls, businesses may need to involve gatekeepers and key influencers including girls’ families, community elders, or religious leaders.

2) Girls are earning and spending money.

Across East Africa, girls are actively saving and spending money. Girls in all 5 countries shared that their sources of income included relatives, and earning through ‘casual jobs’ such as farming, washing clothes, or tailoring. Girls in urban areas – some as young as 12 and 13 years - reported riskier sources of money, such as working in bars and getting money from much older “boyfriends” or “sugar daddies.”

Girls reported spending their money on everyday purchases such as snacks, clothing, school stationary, mobile recharge cards, and sanitary pads. Some older adolescents contribute to household expenses such as rent. Many girls save small amounts of money, but are unable to build up their savings due to not having secure places to save.

When it comes to larger household financial decision-making, such as the production and sale of farm produce, parents make the decisions. However, out of school girls aged 17-19 in Nairobi considered themselves to be influential in their parents’ decisions regarding the household’s energy investment. Girls in Tanzania who were earning money were reluctant to tell their parents how much they were earning because they didn’t want to be pressured into spending on family needs.

Businesses should consider: Girls generally have purchasing power for every day purchases, and older girls, especially from poor families, contribute to family purchases. Businesses need to think about marketing to girls as current and future purchasers, and should consider how they can support girls’ financial inclusion, particularly savings.

3) Girls are increasingly accessing media technology and some are using mobile phones

While cell phone access is still limited to mainly older girls in urban areas, there is a clear and rapid trend towards cell phone use amongst girls. For example, most girls interviewed in Rwanda have basic or "dumb" phones, which they use to communicate with family and friends. Girls with smart phones tend to be older urban girls who use them mainly for Facebook and media. Some parents in Rwanda felt that cell phones were a distraction and could put girls at risk of sexual predators.

In Tanzania, parents and girls expressed the benefits of mobile phones for educational purposes and communication with family vs. the risks of surfing the internet and communicating with boys. Girls shared that they generally do not have their own phones, but use their parents’ – especially their mothers’ – phones.

Although Ethiopia’s ICT infrastructure is among the least developed in the region, the girls we spoke with in Addis Ababa and the Amhara region reported that almost all 17-19 year-old girls own their own mobile phones, and 13-16 year-old girls in rural areas could easily use phones belonging to their parents and older siblings. Ethiopian girls used their phones to call and text family, listen to the radio, play games, take pictures, access Facebook, and access information.

Businesses should consider: Mobile phones and digital media have huge potential to provide information and services for girls at scale, but access depends on local context.

4) Health is of paramount importance to girls and their families, but cost is the main barrier to spending money on healthcare or health insurance.

Girls and their mothers in Rwanda felt that ignorance about reproductive health makes girls vulnerable. The major health concerns raised by Rwandan girls were related to sexual and reproductive health: unwanted pregnancy, HIV/AIDs, and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Girls and their parents in Tanzania felt that girls could easily obtain health information from friends, TV, and radio. Mothers in Tanzania reported that medical care and health insurance was prohibitively expensive, and so they would substitute where they could, for example using cloth instead of sanitary pads, or using local herbal remedies rather than buying medicine.

In Ethiopia, girls across all age groups reported that being healthy is the key to completing their education and being able to earn. They wanted access to better reproductive health information, especially preventing pregnancy and HIV. Money was commonly mentioned as a barrier to accessing health information and healthcare services.

Businesses should consider: Businesses in the health or healthcare sector should understand where girls are accessing health information, real and perceived affordability constraints, and what the health priorities are for girls and their families.

5) Girls have large domestic burdens and experience time poverty.

Time poverty due to large domestic burdens is a significant problem for many girls in East Africa. In Kenya, rural girls aged 14-19 engaged in farming activities at their homes and considered them part of the regular chores. Older out-of-school girls sometimes participate in agricultural activities to earn wages. In Nairobi, girls aged 10-16 were tasked with running daily errands to source household cooking fuel.

In rural Uganda, girls in school aged 14-16 reported that they help their mothers cook for the family once they return home from school in the evening. One group of 13-14 year-old girls told us that they didn't mind spending time collecting firewood because they socialized while collecting. Out of school girls aged 17-19 reported that they often had to multitask: cooking with firewood while washing clothes and cleaning the house.

In urban Uganda, older girls who attended vocational training preferred to take boda-bodas to the training centre to save time, given their mornings were dedicated to chores. However younger girls preferred to walk home from school to avoid chores.

Businesses should consider: Businesses whose offerings require girls to take on additional activities should make sure these are realistic given girls’ other time responsibilities. Those who aim to save girls time should also consider possible negative impacts, for example reducing girls’ opportunities to socialize with their peers.

This blog is a part of the September 2017 series on Empowering women, in partnership with SPRING.

Read the full series for insights on business models that empower girls and women, a new analysis of gender impacts of value chain interventions, tips on gender-lens investing and many inspiring personal stories from women.