The importance of an intermediary when negotiating an Inclusive Business partnership

As the CEO at Business for Development and after eight years of executing, advocating, and brokering inclusive business partnerships, I have learnt it is vitally important that there is an intermediary when negotiating a partnership to develop inclusive business. Without an intermediary often one party’s needs are met more than the others, which in turn can cause the partnership to fail.

I have often likened the role of an intermediary as being a tightrope walker. As you teeter along this rope of negotiations between parties (community and business) there are competing forces. On one side you have the community that are seeking ways to pull themselves out of poverty, on the other side tipping the balance are businesses that are seeking commercial viability and more profit. To compound this, there can be an air of mistrust between parties.

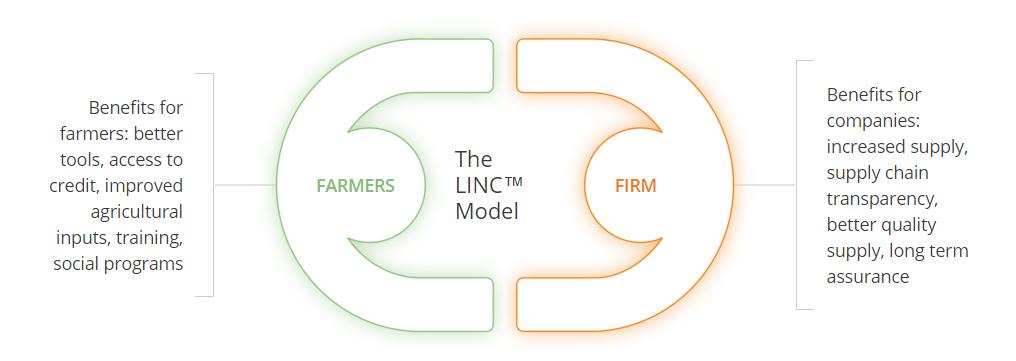

From our experience at Business for Development and sitting with smallholder farmers in rural villages across Asia, Africa and the Pacific and then also discussing with CEOs at multinational food companies we have developed the LINC™ (Long-term Inclusive Commercial Enterprise) architecture. This, as an intermediary, enables us to negotiate on this rope between social impact and commercial interest with the end goal to insuring commercial sustainability.

In Asia-Pacific, Business for Development has acted as an intermediary for:

- Ironbark Citrus in partnership with MMG to develop an inclusive business in Laos to enable farmers to earn greater incomes by supplying citrus fruits to regional markets;

- PepsiCo to procure potato from poor smallholder farmers in Myanmar;

- Mondelēz International to procure cocoa from smallholder farmers from Papua New Guinea.

For example, Business for Development was asked by Base Titanium to help build agricultural opportunities for the farmers around its mine site in Kenya. As a result, Business for Development built a partnership between Cotton On Group, Base Titanium and local smallholder farmers to pilot a program to grow cotton. Working with 200 farming families, the aim was to build a community livelihoods project which increased income to $1500 per annum from current subsistence farming and to ensure there is a sustainable source of cotton. Without an intermediary the fine balance, where all parties feel they have benefited from the partnership, would unlikely have been achieved.

Years of working in this space has proven time and time again that it is integral in the development of an inclusive business that there is an intermediary. As a result the partnership is more likely to flourish and scale-up, with significant impact for poor communities on the ground and commercial benefits for business.