Last mile distribution at the BoP

Four billion low-income people live at the base of the pyramid (BoP). This barely tapped market is increasingly heralded for its sheer size, its potential to drive profit and growth and the opportunities it presents for millions of poor households to access beneficial products. Durable goods – such as solar lanterns, water purifiers, home packages or latrines – and consumer goods – such as fortified foods, anti-bacterial soaps, or mosquito repellents – represent both great life-changing opportunities and fantastic market potential… provided they find the right distribution channel!

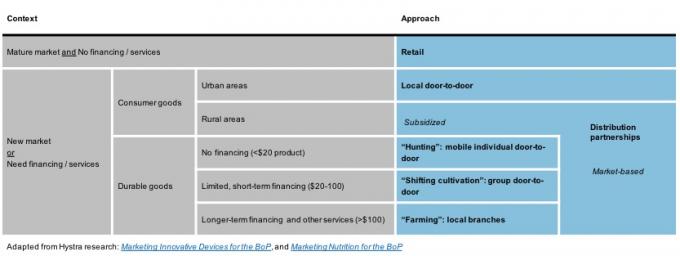

Despite its promise of growth and development, the BoP market is hard-to-reach and still faces a number of well-known challenges: small transactions, poor infrastructure, dispersed consumers, or low product awareness. As a consequence, too few beneficial products are actually reaching the people who need them. Fortunately, a few encouraging exceptions have been successful in distributing products at the BoP and can be learnt from. The six different approaches summarised in the table below can work in specific contexts, depending on the maturity of the market (how strong is existing product demand?), its density (are there enough people within reach to support a sales person income?), and the type of product sold (do they require financing or additional services such as delivery, installation and maintenance?).

Six distribution models

Retail

Traditional distribution channels are generally the most cost-efficient to reach the BoP, costing 20 to 30% of consumer prices at scale, including advertising, channel management, and margins of wholesalers, resellers and retailers. Yet for distributors of new products, a key challenge is to get their brand accepted and promoted by retailers. In addition, retail rarely allows providing credit or services (e.g., home delivery, maintenance, etc.). There are successful examples of retail sales of beneficial products at the BoP, both for consumer goods – such as PKL’s nutritious products in Côte d’Ivoire – and low-cost devices such as improved cook stoves and solar lanterns. For instance the Awango initiative by Total sells solar products through the company’s gas station network, and has become the largest commercial distributor of solar lanterns in the developing world, with over 1.4 million units sold in 33 countries as of early 2016.

Local door-to-door

Setting up a local door-to-door sales force can help create brand recognition in new markets and bring additional value through home delivery that retail could not provide. However, the sustainability of such channels requires that each sales person generates enough revenue locally to cover their costs – sales need to be recurring and client density high enough. There is evidence that this model only works sustainably for consumer goods in dense urban areas. For example, Nutri’zaza sales ladies in Madagascar sell ready-to-eat infant fortified porridge at the doorstep of their clients daily, offering convenience that mothers are willing to pay for: they reach penetration of over 50% in areas where they deliver the products.

Distributionb Partnerships

Leveraging existing networks can be attractive for the distribution of both consumer and durable goods, for different reasons. For consumer goods that are not yet in demand, in rural areas, the only financially sustainable way to use door-to-door is to leverage a pre-existing, credible network. BRAC has leveraged their trusted, already paid for, network of 90,000 health workers to effectively sell Pushtikona multi-nutrient powders in rural Bangladesh, distributing over a million sachets per month. For durable goods, distribution partnerships can be particularly attractive with organisations that combine a large existing consumer base with financing capacities – such as micro-finance institutions, rural banks, utilities, or some agro-companies. In East Africa, One Acre Fund, an NGO distributing agro-inputs on credit to over 200,000 farmers per year, has added improved cookstoves and Greenlight Planet solar lights to its product mix with simple top-up loans for farmers, selling over 100,000 lights within a few years. In India, the MFI IVDP has distributed PureIt water filters and d.light solar lanterns on credit to over 100,000 households. However, these partnerships can be double-sided: Hystra research shows that only one in 10 to 20 partnerships with financial institutions reaches the expected sales volume for distributors of durable goods. In addition, some clients might feel pushed into buying (which is good for immediate sales but bad for social impact, as these clients are unlikely to use the product). Therefore, this distribution option must be carefully considered.

"Hunting": Mobile individual door-to-door

Organisations selling simple low-cost devices (less than $20) such as Toyola improved cookstoves in Ghana, employ full-time, mobile sales agents each serving several thousands of households each year. They cover extensive, non-exclusive areas, leveraging retailers or lead generators among local villagers (called “evangelists” at Toyola), to aggregate demand. They will be successful – Toyola has profitably sold 600,000 stoves as of early 2016 – as long as the products they promote are new and cannot be found in traditional distribution channels, and will probably need to switch products or revise their business model when this happens (Toyola sales agents, initially selling mostly via door-to-door and “evangelists” in rural areas, now make most of their sales to retailers).

"Shifting cultivation": mobile group door-to-door

For more complex and expensive durable goods that require credit but limited service (typically $20-100 products), the most adapted business model is that of a specialised marketing and sales team covering a region until they have achieved their target penetration and finish collecting loan payments, before they shift to the next area. They only go back once when replacement needs arise. The Paradigm Project has implemented such a model in Kenya, where its dedicated salesforce has sold over 175,000 beneficial products (90% of which are improved cookstoves) as of early 2016, including 40,000 on credit. Find out more about the different types of door-door networks in the publication Best Practices for Door-to-door Distribution.

"Farming": Local branches

For goods above $100 (e.g., solar home systems or home improvement packages), successful organisations set up local branches from where their sales agents operate, with each agent serving only a few hundred clients a year. Grameen Shakti has sold more than 1.5 million solar home systems in Bangladesh, each worth over $100, through local branches. Patrimonio Hoy, an initiative by the cement manufacturer CEMEX which has renovated over 500,000 homes of low-income families around Mexico City through projects which cost around $1000, also uses the local branch model. These organisations offer credit and maintain regular contact throughout the year to ensure after-sales service and customer satisfaction. They often take over a decade to reach full penetration in a given area. Given their limited reach (typically a radius of 50km max around each branch), the main lever to increase sales is to extend the range of complementary products and services to holistically fulfil their clients’ needs, as Grameen Shakti is now doing by adding DC appliances to the products it can offer to its clients.

These approaches are all likely to evolve over time with technological progress and market maturity. For example, lately, in solar home systems, the need for proximity of money collectors and technicians is declining thanks to pay-as-you-go solutions for payment and technological progress allowing faster installation and limited maintenance. So the distribution systems are likely to evolve from ‘farming’ through local branches to ‘shifting cultivation’ models. Setting up distribution channels is costly in terms of time and resources, so making the right choice is key. The right distribution strategy, as we have seen above, depends mainly on the type of product sold (requiring financing and services, or not), the market density, and its maturity (requiring demand creation, or not), and. In addition, getting the marketing strategy right is crucial too. Typically, mass media advertising can result in short term sales increase, but long-term commercial success will rather come from below-the-line marketing. Word of mouth, practical demonstrations, aspirational branding, usage by trusted community leaders, product reliability, and the opportunity to try a product before purchase have all been shown to be particularly important in BoP sales.

The best strategy is still not enough to ensure success

Triggering new purchasing behaviour from risk averse clients, and doing so viably in hard-and-expensive-to-reach areas, also requires perfect execution of the sales strategy. And there, the devil lies in the details, both on distribution (e.g., how many sales people do you need, to cover what territory? With what vehicles? What incentives to motivate them to sell? What IT system to support them?) and marketing (e.g., how to ensure all sales people execute the product pitch as well? How to ensure client satisfaction and encourage word of mouth?). In the end, it is key to get right both the strategy to sell those products, and the execution. A tricky duet that only a few have cracked, but on which many have already gathered critical insights. Learning from past successes and failures will be key to accelerate the success of new players, and ultimately bring more of these life-changing products to those who need them most, sustainably and for the long term. The three part webinar series ‘How to viably market and distribute beneficial products to the BoP’ draws on on-ground research to provide invaluable guidance on the subject from developing a winning value proposition to setting up effective delivery mechanisms.