Mark Bennett - obituary of an education entrepreneur

A little under two years ago, Mark Bennett was forced to mark his sixtieth birthday by gathering his employees together and telling them that the company was on the verge of running out of money. He was, as usual, working every hour he could to ensure its survival. For six weeks he had met with three or four potential partners a day, and impressed upon them how iSchool could transform education, and perhaps healthcare and agriculture too, across vast swathes of the world. In a rather Victorian way, this well-travelled, slightly creased-looking Englishman in his navy blue suit had spoken of Progress, and Technology, and pointed at the large map of Africa on the wall of his office with expansion in his eyes. Like in Kipling's famous tribute to Leander Starr Jameson, another Englishman who faced heroic misfortune in Africa, he had made a heap of all his winnings – the millions of dollars he made from building up a successful telecoms company – and risked it on one turn of pitch and toss.

And it was certainly a gamble. Although there was no doubt that Africa needed and wanted better education, and Mark Bennett for one never doubted that technology was the way to deliver it, whether money could be found in the continent’s ramshackle school systems to pay for it was a gigantic unknown. And money had to be found. iSchool was no $5-a-month charity: it had to be financially sustainable, it had to be profitable as a business. Not because Mark himself cared for riches, but because financial sustainability was the only way iSchool could reach the sort of scale that it deserved to reach, the sort of scale that would justify the hundreds of person-years of development that had already gone into the product.

Back in 2004, when he and a colleague had founded AfriConnect to provide Internet access in a region where it was still needlessly lacking, they had been able to start small, beginning with a server and a pair of aerials on a single roof and using the revenue from each new batch of customers to buy new servers and new aerials, growing the company bit by bit into a national brand. But in the education business it was different. You couldn't go into an entire school, let alone the hundreds of schools Mark Bennett envisaged, with only half a curriculum. At least, not in his vision. He had established back in his AfriConnect days that the educational materials already out there on the web did not fit well with African learners and their curricula, but commissioning 5000 lessons of his own, many of them accompanied by beautifully illustrated and narrated stories and quizzes, had not come cheap. Nor had setting up the hardware, supplying class sets of networked laptops to eight pilot schools who tested them to destruction, and replacing the laptops with standalone 7-inch tablets when it became clear that this was the way forward. Prospective release dates came and went, salesmen were hired, a teacher training suite was furnished, new lesson-writers, artists, translators and narrators were hired as fast as management capacity would allow, and cash was burned with the rate of a rocket engine firing up for launch – yet still we were months away from a finished product.

Thus Mark Bennett was on the verge of losing, and starting again almost at his beginnings – the technology enthusiast who had left England in the 1980s with his young family, for a university job helping to introduce computers to Zambia. Back then Zambia was in such a poor state of development that he had to drive across the border to Zimbabwe to buy such basics as orange squash. Three decades on, his office was surrounded by new shopping malls, and thanks to AfriConnect, Zambians were surfing the Internet on a modern 4G network. His children had grown up and were back in England, but he was still surrounded by young people to whom he had been so supportive – in his stiff yet deeply sincere way – that they had come to view him almost as family. Mark Bennett was not only a highly-driven entrepreneur, but a thoroughly decent man.

It frustrated him intensely when things went wrong, which they continuously did. In Zambia he met with not only Triumph and Disaster, but an even more insidious impostor, Mediocrity, to which in thirty years he never himself showed the slightest sign of succumbing. And when other people didn't do their jobs properly, he could be remarkably patient, chalking up their incompetence simply as another technical problem in need of a solution.

iSchool was his ultimate solution. As manager of AfriConnect he had seen first-hand what a terrible job Africa's education systems did of creating employable citizens: fix those, and development could hardly fail to follow. The improvements had to start not at the decrepit University of Zambia, where Mark had begun his overseas career, but right at the grass roots, in the dim little primary schools tucked into the corners of villages and slums, where teachers who had never known any better were still inflicting mindless rote learning on pupils in languages they didn't understand. Technology itself could not change that. Thanks to a clever system of rotation that allowed a school to get by with only a few tablets per class, pupils in an iSchool classroom spent less than a fifth of their time looking at screens anyway. But when the technology was delivered as part of a package which, unlike most technology projects in developing countries, had training and support at its core, it might open pupils' and teachers' eyes to a new way of learning. A way that was fun and interactive, a way that would teach learners to think for themselves, a way to make education more than an ever-deepening cycle of repetition. Though Mark himself never found the time to master anything other than slightly-mumbled English, he put over two million words of translated text in front of Zambian children in their own languages (substantially increasing the total body of literature that exists in some of these languages), with pictures and narration to ease struggling learners gently but effectively into literacy.

Mark was not a typical international development figure. He never claimed that he was trying to save Africa, merely get it working the way it should. He based himself in Zambia, flying home to England only for occasional weeks of meetings, rather than the other way round. Lusaka was not a loveable city, but there were more problems he could help solve there, and those kept him satisfactorily busy. He was also at times a solitary figure, though he attended the interminable meetings and workshops if he thought he might find people there who could help him with solutions to the many problems he had taken it upon himself to solve. He engaged politely with the government departments who wrote promoting ICT into their policies but never into their budgets, the visiting academics from his home town of Cambridge who studied how to make education more engaging then handed out 120-page manuals on the subject, and the bankers who offered to lend him money to finish development of his untested product if only he could give them definite sales figures, which of course he couldn’t. And when all these people failed to provide the solutions he wanted, he continued to throw literally everything he had at coming up with his own.

He stuck bloodily to his visions right up til the point where compromise was utterly unavoidable. At first iSchool was to market its tablets in nothing less than full class sets, accompanied by the full package of teacher training, electrification and whatever else a school needed – there was no other way of ensuring the material would be used to best effect. Eventually, with the company desperate for revenue, and teachers and parents eager to get their own hands on the material, he reluctantly agreed to sell standalone tablets too. Not every school could afford to invest in a whole suite of technology, even one whose cost, when broken down per pupil per month, could be measured in cents. Indeed, the majority of schools could afford almost nothing at all. There were solutions to that, Mark was sure. He held meetings with microfinance providers and aid agencies, investigated how schools could earn revenue as Internet cafes, and scattered his dining table with ever-cheaper pieces of experimental Chinese hardware to see how costs might be brought down. Fully teched-out classrooms remained the ideal, but in the meantime a teacher delivering a good lesson from a lone tablet was a lot better than one who skipped class (as Zambian teachers did, 40% of the time) for lack of inspiration.

On a personal level, Mark never breathed a word about his losses, continuing to write cheques for friends' and employees' school fees and medical bills even as the debts mounted up. Yet in ever-more-frustrated meetings in the office boardroom, he would tell us that we could not afford to delay the launch any longer, we simply had to ship, we had to get the product ready next month, even if six months' work remained. At more than one point I imagined myself writing an obituary on this forum, not of Mark Bennett but of his company. Laced with quotes from that other tribute of Kipling’s to heroic failure abroad - "watch Sloth and Heathen folly, bring all your hopes to nought!" - it would have lamented the overambition of the company’s founder, and the lack of ambition from the stakeholders (myself included) who had failed to do enough to support him.

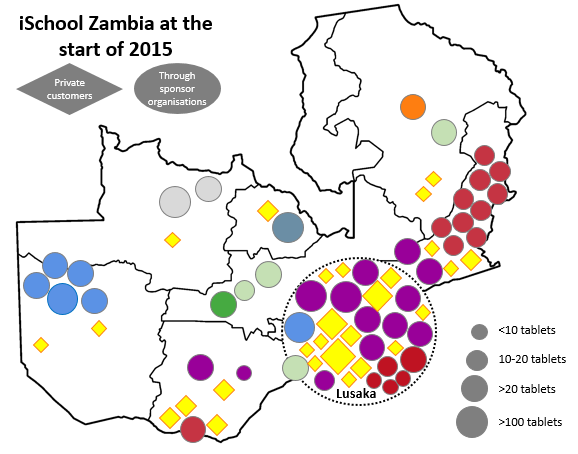

Yet iSchool did not fail. At the end of 2013, after a life-saving injection of investment capital and an exhausting final push in the production department, iSchool released its Zambian educational tablet, the ZEduPad. It was not done with quite the flair of Steve Jobs, but the ingredients were there – the cool white headphones, the flagship store, the sense that this was something the world had not seen before. And, a little to my surprise, people bought them. Not in the sort of gigantic numbers that would have given poor Mark some respite from the anxious meetings with potential business partners and investors, but enough to show that this was indeed a product people were willing to pay for. A year on, iSchool is being used in nearly a hundred schools across Zambia (see map), as well as many hundreds of homes.

Mark never imagined that a successful roll-out in Zambia would be the end of it, though. In the production department we were already going through all our Zambian lesson materials altering maps, flags and names in order to turn the product into something that could work in any African country; tweaking the layouts so that they would work on different devices; and adding health and farming lessons to make the ZEduPad useful not just to schoolchildren but to their parents too. As soon as possible we were going into farms and clinics; onto smartphones; into Zimbabwe, Kenya, Botswana, Nigeria, South Africa and a dozen of the other countries on his map. Mark never prioritised if he could help it. There were too many problems that needed to be solved right away.

I saw Mark for the last time ten days ago. Though it was a Sunday morning and he seemed a little unwell, he was, as usual, sitting at his desk busy at work - though not too busy to get up and offer a cup of tea. That week, iSchool had completed its first major international sale, to a group of schools in Lesotho. He was also working with a major sponsor to send tablets to children whose education has been disrupted by Ebola in Sierra Leone.

Mark died in hospital the following week, on an atypically grey and rainy Lusaka afternoon. He is survived by a tentatively successful start-up company which, with luck and the perseverance of its many stakeholders, may yet achieve the vast, crazy, essential scale that its founder envisaged.

Even the statisticians whom the aid agencies insisted he hire to try and quantify the impact of his work would probably balk at the task of trying to count the number of people to whom Mark Bennett made a difference, either personally or through his work with AfriConnect and iSchool. The number certainly runs to many tens of thousands. Even at an individual level the ZEduPad's impact is difficult to quantify. In iSchool's pilot studies, attendance went up, literacy scores improved and parents and teachers reported that their kids appeared to be getting more out of school. But the real benefit may appear only in fifteen or twenty years' time, when some of today's pupils go into the teaching profession themselves, think back to their own schooling and remember that learning can be engaging and fun.