Partnership brokering in action: how Bijoy Switches became an inclusive SME

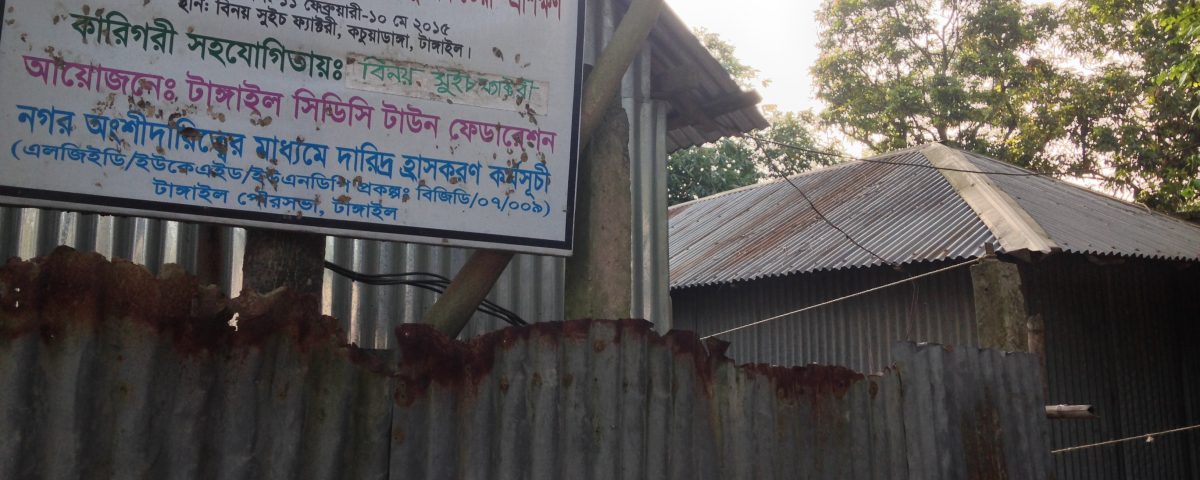

Tangail is a small town by Bangladeshi standards. From the main street it is a short drive to a quiet lane lined with bamboo fences on either side, but busy with people walking and children playing. Opening a gate, you reach a small compound with half a dozen modest buildings. This is the home of Bijoy Switches, a small business making their own range of household electrical components.

Peering into the buildings you see a range of simple machines for molding plastic casings and milling metal parts. In another one, a group of women sit on a matt assembling the parts and chatting to each other.

The owner worked from the age of 12 in various industries, including making electrical switches and other plastic fittings for household use. After 13 years as an employee he took a loan and set up his own small business.

Bijoy Switches now has 30 employees, mostly women, who have all been trained on the job and work in the business. They are all from the local community. The owners says his wages are not high, but he takes care to treat his staff well and is very flexible about when he pays them so that they can respond to their family’s needs for money as they arise.

The employees said that they like working for Bijoy because it is very local and they have no travel costs. It is a safe environment and they say that the owner is a very good man and that they are very glad to be working there.

It is a happy place and a nice little case study of the importance of small businesses to creating jobs and empowering women economically. However I am sharing this success story because there is more to it than that.

The scene shifts to an office in the Town Hall a few streets away. The manager of the local office of the Urban Partnerships for Poverty Reduction Project (UPPR) explains why he took me to visit Bijoy. The UPPR programme, managed by UNDP, had helped women to organise themselves into groups of households, and to then express their development needs. Alongside the need for a stronger voice in their own affairs and better infrastructure in their informal housing, which UPPR was able to help provide, they also said that their communities needed health services, education and jobs.

UPPR was not able to provide these things. Which is where the story gets interesting. Instead of ignoring these issues or asking the donor (DFID) for more funds and a change to their logframe, local managers started to identify other service providers in their areas that could meet the communities wider needs, and to broker partnerships between these organisations and the communities. One such collaboration is how Bijoy came to be able to train and employ local women. Other examples in many of the 2,500 poor urban communities in 23 towns and cities across Bangladesh that UPPR has support since 2008, include health service providers, government departments, training institutions and companies large and small.

Earlier this year I was commissioned to undertake a study of these collaborations for UNDP. I calculated that UPPR had brokered partnerships with at least 450 partner organizations, which could easily have benefited 750,000 people and delivered services of the value of BDT 3,200 m (USD $41 m) to these communities. I also decided that a good number of these partnerships have a very good chance of sustaining well beyond the end of the UPPR programme in mid-2015.

I don’t know about you, but occasionally I come across examples that I feel compelled to share with as many people as I can. This is definitely one such example. To me, it is a fantastic example of ‘doing development differently’ through the power of partnership brokering. The approach was responsive to people’s needs, flexible, adaptive and it promotes efficiency in the use of development funds. It is a concept that needs to be discussed and copied. With UNDP’s kind permission I have written a paper about UPPR’s partnership, which has been published by the Partnership Broker’s Association on their website. Please do read it and share it – it will help us all to meet the ambition captured by the SDGs.

Please go to the Partnership Brokers Association website for my paper.

The report for UNDP on which this paper is based can be found here at the UPPR website.