#FarmVoices: Capturing farmers’ voices for improved monitoring and better decision-making

Voices That Count is a collaborative network of experts and practitioners who use narrative approaches to understand complex realities within organisations or projects. We support not-for-profit, public, academic and social enterprises to generate actionable insights and stimulate collaboration for social impact. Capturing the voice of people and facilitating collective sensemaking in complex change processes is central to all our work.

Perceptions and real-life experiences of farmers are crucial data to understand the complex and diverse dynamics that are at play in membership-based farmer organisations. Facts and numbers alone do not always provide the nuance of complex realities and of the different perspectives that exist across subgroups. Also, in discussions between the different stakeholders across the agricultural chain it is often a challenge to include the voices of famers, beyond the farmer leaders, into monitoring, learning and decision-making processes.

Imagine collecting hundreds of personal experiences (micro-narratives) from farmers about how they perceive their organisation and trade relations. Instead of asking peoples’ opinion through a set of a pre-defined questions, we listen to farmers and capture what matters to them. After farmers share their experiences, they self-interpret their own stories based on a set of signifier questions that reveal deeper insights in the context of their experiences. These hundreds and sometimes thousands of micro-narratives and answers to follow-up questions are then entered in a dedicated software, which allows us to visualise patterns. These patterns and the stories behind them then serve as insightful monitoring data and food for discussion and sensemaking at a chain actors’ gatherings, at meetings with farmers, etc.

Examples of farmers’ micro-narratives:

"Since I joined the Kawa Kanzururu cooperative, I no longer have to contend with the many problems I used to have. I can honestly say that, before the cooperative, we really didn’t sell here, in the true sense of the word. I was suffering so much that it felt like I was actually being robbed of my coffee. I had already started uprooting my coffee trees, because I just couldn’t see the point any more. But after selling to the station last season, I was encouraged by the price I got, the shorter distance involved and the tips I picked up at the mico-washing station. This year I’ve even started to replant, because the Kawa Kanzururu cooperative has really motivated me."

"A bowl of coffee berries used to sell at 1300 Ugandan shillings. But nowadays the price has dropped to 1100 shillings. Yet I have to do a lot of work before coming here [to the washing station of the cooperative] to sell them. When you look at those people who sell to fraudsters without much effort being involved in processing the coffee, I think they earn more than us."

“I’m a coffee farmer. Last season I arrived at the micro-washing station at a time when there was no money and I really needed to pay my kids’ school fees. I was promised that the money would be there in two days so I went off and signed a form saying that I had to pay after the two days. Strangely enough, when I went back to the washing station, the chairman told me that he had already used my money in his business.”

This is the essence of #FarmVoices, a narrative pulse developed by Voices That Count: a process and a tool to keep a finger on the pulse by turning individual experiences of farmers into patterns that visualise the bigger picture. It is inspired by the practice of SenseMaker, a method of inquiry that involves collecting and analysing large numbers of story fragments about people’s experiences to make decisions that respond better to needs and opportunities. SenseMaker recognises that personal narratives allow better access to contextualised knowledge.

#FarmVoices can be used as a “one-off” assessment tool but it is at its best when used as a periodic (continuous) method to keep your finger on the pulse of farmer organisations for a capacity strengthening project, an inclusive business initiative or value chain development intervention.

The stories from farmers and the underlying patterns are powerful evidence to inform leaders and managers in their decisions that speak to farmers’ reality. It is equally insightful for business actors to connect with farmer’s reality and understand the dynamics at play.

Farmer cooperatives that used #FarmVoices became, for example, aware of the need for more transparency and communication across the organisation, and got a clearer view on what type of information was key to be shared with their members in order to increase trust within the cooperative. They also got more insights into what led farmers to make conscious choices about selling to the cooperative. For leaders of cooperatives and (international) buyers, reading the stories served as a decision mirror: they became much more aware on how certain choices, e.g. on delivery schedules, affected the farmers.

"Having worked in the agriculture and finance space, most of the monitoring and evaluation methodologies are very intentional: we define the questions and look for answers from farmers. What I did not realize is that we seriously risk losing perspectives that may not covered by our questions and thereby limiting our understanding of farmers’ experiences. After using #FarmVoices in Rwanda, I am convinced that allowing farmers to tell their stories by putting forward issues and events they consider most relevant, is a crucial component of their reality. This information presents great value to all stakeholders who work with them and in the sphere of development as a whole, because after all poverty is a complex lived experience."

Pallavi Hariharan, Environmental & Social Impact Manager, Alterfin"#FarmVoices is a powerful tool, not only for better understanding the perspective of the farmers, but also because the information it generates can be used to trigger deeper discussion even on sensitive issues in a constructive way with all stakeholders in the chain."

Dewi Utami Catur, former M&E manager of Rikolto in Indonesia

What are the key phases in a #FarmVoices process?

The #FarmVoices process always starts with a design stage, during which a choice is made about whose voices need to be heard and, if necessary, a sampling strategy is developed. Although #FarmVoices was developed as a standardised tool, a critical task of the design stage is to align the questions with the context of the farmer organisation (size, structure, crops) and the focus and scope of the narrative pulse. Therefore a decision has to be taken on the prompting question (the opening question that invites people to share their stories) and the follow-up questions (to self-interpret their stories).

At Voices That Count we developed a library of follow-up questions (also called signifiers), framed around (1) the governance of the farmer organisation (2) the performance of the farmer organisation, (3), the benefits for the farmers, and (4) trading relations.

In a second stage, the stories and answers to the signifier questions are collected through an individual or group-based process facilitated by trained story collectors. The data is recorded using paper-based forms or the Collector app on a tablet or mobile phone. The advantage of face-to-face collection is that story collectors can ask additional questions while prompting a story, which can lead to richer stories. Experience also tells us that when the data collection is deliberately structured to engage people in deeper conversations, it shifts their understanding about their context and situation. The collection process itself is equally as important as the results and insights generated.

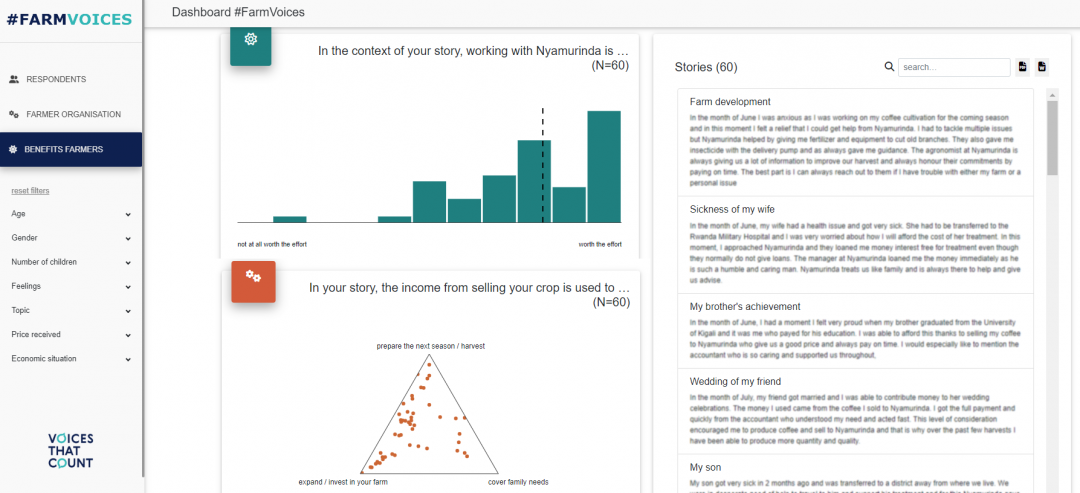

The result of the story collection is a rich dataset, visualised in a tailor-made dashboard in which one easily can detect patterns across the multiple narratives based on the answers to the signifier questions. The analysis starts with a pattern analysis rather than an in-depth reading of individual stories – in order to spot dominant, interesting and surprising patterns, outliers, key differences between groups, and correlations between different signifier questions. During this phase, we identify the main questions, issues and themes that should be further explored during the collective sensemaking workshops.

Sensemaking workshops include those stakeholders who need to make strategic decisions about the farmer organisation or cooperative and/or those will be using the findings in their daily work to adapt the project interventions. An important part of the sensemaking workshop is reading and discussing stories. Collective reading, ‘unpacking’ and discussing the stories is a powerful process that creates new levels of understanding of the context. The collective nature of sensemaking contributes to the uptake of findings by building wider analytical capacity and, in the process, informing decision-making and action.

What makes this narrative approach valuable and unique?

- Experiences, not opinions. The starting point is the personal experience of farmers around the topic of inquiry, and not the collection of opinions or scoring against pre-defined indicators. It is not a collection of long and in-depth stories from a small group of people, as with some other storytelling methods, but a listening exercise gathering day-to-day experiences, moments and events from hundreds and sometimes thousands of stories. From this, we are able to ‘read’ a (production or food) system through the eyes of the farmers.

- Self-interpretation. By answering follow-up questions, storytellers provide further information and give additional layers of meaning to what is expressed in their stories. They make a primary assessment of their own stories and by doing so reduce the bias of external researchers or analysts.

- Visual patterns representing trends and dynamics. Strong clusters, trends, and outliers give rapid insights into the drivers, behaviours, dynamics, contextual factors and actors in people’s lives.

- A unique combination of qualitative and quantitative data, which connect to and complement each other to generate better insights. Narratives are turned into numbers and patterns, which in turn derive meaning and context from the underlying narratives. The SenseMaker software and associated dashboards allow for a rich analytical process.

- Every voice counts equally. Valuing each person’s experience means there is no capture or selection of the best or most significant stories. People share stories and experiences that matter to them, which can be both negative or positive, or a mix of both. Dominant voices are not favoured above others: every voice, every story is used equally to visualise and analyse emerging patterns and trends. It is therefore an ideal method to give equal voice to those people who are often not heard.