Myanmar Belle Company Limited

Myanmar Belle Company produces frozen and dehydrated vegetables for export to Japan. Through its contract farming model, it improves the lives of 3,500 smallholder farmers. In addition, it provides income and training opportunities to female factory workers.

To start, can you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Ye Myint Maung, and I am the Chairman of Myanmar Belle Company. I founded it as a trading company in 1995 and expanded into contract farming in 2010. Now, we produce different kinds of frozen and dehydrated vegetables: cabbage, carrots, mangoes, spinach, okra, taro, and kidney beans.

Why did you expand into contract farming?

Farmers are the backbone of our country. I want to provide them with a reliable market.

How does your farming model work?

Before we draw up contracts, we estimate the amount farmers will produce per acre and the profit they will make. In the contracts, we guarantee to buy all these crops at a fixed price. If they produce more, we buy more. If the weather is bad and they make losses, we compensate them by half. In addition, we provide inputs and training. To help them cover additional costs for living expenses and labour, we run a microfinance institute.

How else do you include low-income communities?

After we have purchased the crops from the farmers, we process them in our factories in Heho, Southern Shan State and Nay Pyi Taw. Instead of producing raw materials for China, we export value-added products – frozen and dehydrated fruits and vegetables – to Japan. This creates jobs in the country.

How do farmers benefit from your business model?

They can double or even quadruple their income. This also spurs rural development in the regions we farm in: Shan State and the surroundings of Mandalay and Nay Piy Taw. In Kayah, we provided an alternative to opium cultivation until we stopped working there this year.

How does your model spur rural development?

Most importantly, we jointly invest in education.

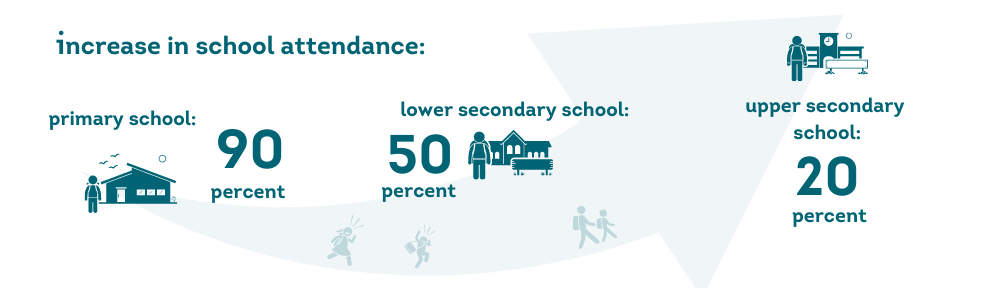

In the contracts, all farmers agree to spend twenty per cent of their profits on the education of their children. We also provide scholarships. As a result, the share of children attending primary school has increased by ninety per cent in the villages we are working in. The numbers have doubled for lower secondary school students, and there is a twenty per cent increase in upper secondary school attendance. Some farmers even send their kids to university. When they grow up, we offer them internships and hire them back.

What about the factory workers?

They can earn a stable income of 150 to 1,500 US dollars per month without having to emigrate. In addition, we offer training opportunities and scholarships. Some travel to Japan for their education; others go to university in Myanmar. In return for the scholarships, they commit to working for us for three to five years after graduating.

How many people do you reach?

We work with 3,500 contract farmers, including 2,800 women. In addition, we employ eight hundred to one thousand staff members.

Seventy per cent of our employees are women. Even on the management board, we have more women than men: seventy percent. Also, 55 percent of our employees come from ethnic minority groups. It is important for me to create opportunities for them.

How do you measure the impact you create?

We measure it by ESG standards, which I also recommend to other entrepreneurs. This helps us set our strategy and evaluate it comprehensively.

Our main metrics are the number of households reached, the productivity and profitability of farmers, and the education of their children. We want to measure long-term changes.

Where do you sell your products?

We mostly export to Japan. I lived there for twenty years, so I know the country very well. The demand for our products is high there. Japanese children, for example, mix dehydrated carrots or cabbage into their rice if they don’t want to eat fresh vegetables.

Food safety standards in Japan are very high. When we have fully mastered all of them, we can export our products anywhere.

Why don’t you produce for the domestic market in Myanmar as well?

There is little demand for frozen and dehydrated food here. Most people buy fresh vegetables instead. In addition, we can pay higher prices to the farmers if we export to Japan.

What is your value proposition to consumers?

We want to make sure that all of our crops are safe for everybody to consume. This is why all of our products are chemical-free; we have just received our GlobalG.A.P. certification and comply with a number of other standards. To ensure compliance, we train our staff and farmers on pest control and post-harvesting techniques.

Can you share the annual revenue of Myanmar Belle Company?

Our annual revenue has been increasing over the years, from five million US dollars in 2016 to six million dollars in 2018 and eight million dollars in 2020. Eighty per cent of our revenue is from contract farming, the remainder from my retail business.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, our revenue has continued to grow. We started to prepare safety protocols as soon as the cases went up in China. So, we were able to keep operating throughout the crisis.

What are your plans for the next few years?

We want to reach 5,000 farming families within the next two years.

In addition, we want to digitise most of our processes to gather more reliable field data. We will track our products from farm to factory and monitor all farm inputs. This will help us improve food safety and cut costs for everyone.

We will also expand our product range to include pickles, pastes and seasoning. Our aim is to buy all the crops farmers are producing.

What can you point to in your track record that demonstrates the potential for profitable growth?

Myanmar Belle Company is a pioneer: We are the first producer of dehydrated and frozen vegetables in Myanmar. In scaling, we create triple wins for the company, the communities, and the consumers. When we open new factories and buy more raw materials, we reach more workers and farming families. At the same time, more consumers gain access to safe and affordable products made in Myanmar.

What do you need to realise these plans?

We are looking for additional investment, mostly for our IT projects and to develop new products.

What challenges have you and your company overcome?

It has been challenging to convince farmers to follow our regulations. We had to demonstrate to them that following the guidelines increased their yields and their profits.

It is also challenging to find skilled workers. Many talented people study abroad, but do not return to Myanmar. The scholarships we provide are a way to overcome this difficulty.

Inputs have become pricey, too, especially because we need to use new seeds to adapt to global warming. We encourage farmers to use home-made fertilisers, which are also better for the environment.

What motivates you to keep going despite these challenges?

Farmers are the backbone of our country, and I really want to support them. I come from a farming family myself, so this is important to me. In addition, I want to see more ‘made in Myanmar’ products around the world.

What recommendations do you have for other inclusive business companies?

My business is based on agriculture and food. I believe that eating habits depend on two factors: education and money. In a developing country like ours, we need to enable people to choose healthy food instead of only eating for survival.

The Impact Stories are produced by the Inclusive Business Action Network (iBAN). They are created in close collaboration with the highlighted entrepreneurs and teams. The production of this Impact Story has been led by Susann Tischendorf (concept), Sara Karnas (video), Katharina Münster (text and infographics), Christopher Malapitan (illustrations), and Alexandra Harris (editing). The music is royalty free. All photographs are courtesy of Myanmar Belle Company.

Updated: 11/2021.