Micro-franchising for development: The example of Krishi Utsho in Bangladesh

The development world has long embraced micro-finance, and there is a lot of hype about micro-entrepreneurs, but what exactly is a micro-franchise?

A micro-what?

Micro-franchising "has its roots in traditional franchising, which is the practice of copying a successful business and replicating it at another location by following a consistent set of well-defined processes and procedures." CARE Bangladesh’s social enterprise Krishi Utsho demonstrates how micro-franchises can complement traditional market-based approaches to ending poverty.

Krishi Utsho

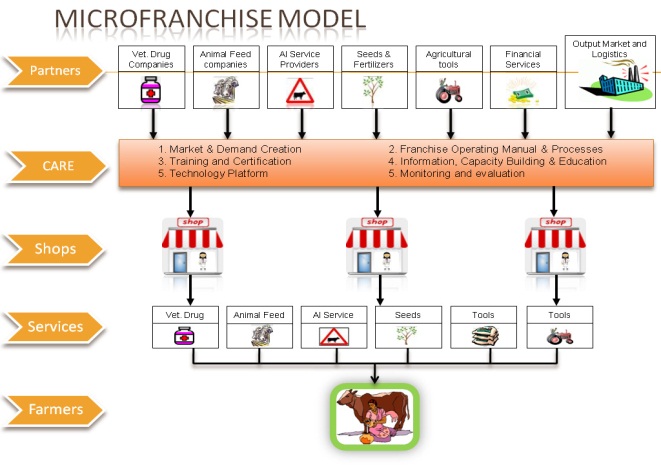

In technical terms, Krishi Utsho could be referred to as an “agro-input micro-franchise network.” Less densely, Krishi Utsho is a system of stores, all linked by a common brand but owned by individuals, which sell products like feed, seed or veterinary medicines to farmers. Think McDonald’s but with higher social impact.

CARE Bangladesh is the franchiser: it owns Krishi Utsho. Krishi Utsho rents its brand to franchise holders for an annual fee and a percentage of sales revenue. It also arranges the distribution of key products from wholesalers to individual shops, ensuring regularity of supply. Franchisees, in turn, agree to maintain minimum quality standards.

In the case of Krishi Utsho, the micro-franchise is also a social enterprise, with both financial and social returns. Its 31 shops (anticipated to grow to 70 shops by the end of 2015) across rural Bangladesh play an important distributor role in connecting farmers to markets. Currently, many mainstream brands do not sell appropriate products for smallholders (e.g. only selling sizes they cannot afford) and unbranded venders sell low-quality goods (e.g. fertiliser that doesn’t work or feed that is adulterated.) The franchise model means local farmers can go to any Krishi Utsho outlet and be confident that they can find products that work in the quantity that they need.

The diagram below demonstrates how the Krishi Utsho franchises connect farmers and input brands.

Opportunities:

Micro-franchises offer a valuable addition to traditional value chain development or M4P (Making Markets Work for the Poor) strategies by not only facilitating market change, but also actively filling a market gap. In the case of Krishi Utsho, everyone from farmers to input brands benefit.

- Farmers benefit from regular access to high-quality services and goods which are specifically marketed for smallholders.

- Franchise holders benefit from business training and an increased consumer base, with a growth during the pilot period of over 50 per cent more customers.

- Brands are able to cross “the final mile” and reach base of the pyramid markets which they would otherwise be unable to access.

- CARE, as the franchiser, is able to establish a social enterprise which is sustainable, scalable, and, in the long-term, independent of donor funding (as the organisation has already achieved in Bangladesh with the JITA rural sales model).

Challenges:

- Value chain financing: Though franchisees are generally better off than small-scale farmers, their monthly incomes still only average $365 per month. In order to buy into the Krishi Utsho brand, or to expand their stores after they have done so, they need higher access to capital. CARE is currently exploring ways of facilitating finance for franchisees.

- Gender: While the majority of the small-scale farmers that benefit from Krishi Utsho are women, not unexpectedly, women found it more difficult to take advantage of the franchisee opportunity. This is in part due to strong social mores preventing women working in public, and in part due to lack of access to appropriate education or finance. Currently, one franchisee is a woman; however, CARE is providing technical and managerial trainings to new female recruits in an effort to boost recruitment. In the long term, women’s full participation in the value chain will depend on altering social norms on women’s role in the economy.

Conclusion:

Micro-franchising can provide “micro-entrepreneurs with a proven business model and the chance to benefit from the best practices of hundreds or thousands of other micro-entrepreneurs, as well as from the purchasing power and scale of the franchisor,” writes Tobias Hurlimann. Micro-franchises are not a replacement for other market engagement strategies, but they do offer substantial benefits that enterprise development strategies may not: a scalable, replicable model, ongoing business development for training for franchisees, and the benefit of a network rather than many micro-entrepreneurs working in isolation. Micro-franchising may be an idea whose time has come.

Background:

CARE International fights poverty and injustice in more than 80 countries around the world. Krishi Utsho is supported by the Brooks Foundation and the UK Department for International Development. For more information about Krishi Utsho, read “Krishi Utsho: The Building of an Agro-input microfranchise network in Rural Bangladesh.” For more information about CARE’s market engagement work in Bangladesh, read “In profit and out of poverty: The business case for engaging with poor farmers in Bangladesh’s dairy sector” or “What your BOP strategy is missing: A gender lens”.

About the author:

Alexa Roscoe is a Private Sector Advisor at CARE International UK. To read more of her blogs visit CARE Insights or follow her on Twitter @AlexaRoscoe.